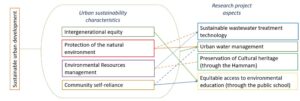

Reflexive exercise I: Urban sustainability – Urban sustainable development

The first exercise is centered around a key element that cut across, to varying degrees, al the research projects of the doctoral candidates: the relationship with the notion of urban sustainability.

Thus, the following question was posed: “How does your research connect to the notion of urban sustainability? As a general reference to deal with this question, the doctoral students were asked to consider the following definition of urban sustainability:

What is the meaning of the term “urban sustainability”? It may help to first compare it to “sustainable urban development.” The meanings of these two terms are very close and are often used interchangeably in the literature (cf. Richardson 1994). One way of distinguishing them, however, is to think of sustainability as describing a desirable state or set of conditions that persists over time. In contrast, the word “development” in the term “sustainable urban development” implies a process by which sustainability can be attained.

Source: Maclaren, V. W. (1956) Urban sustainability reporting. Journal of the American Planning Association 62(2): 184-202. Quote pages: 185-86.

“Mapping” of the research projects in relation to the concepts of urban sustainability and urban sustainable development. Based on the distinction between these two terms found in the quote indicated above, the doctoral candidates were asked to think about whether their research projects relate closer to one or the other notion. To end, policy-making was to be deemed as a continuum connecting sustainable urban development (consulting the “reasoning” providing the basis for actions and measures and thus being “practice-oriented”) at one end, and urban sustainability (consulting the outcome of actions and measures and thus being”materiality-oriented”) at the other.